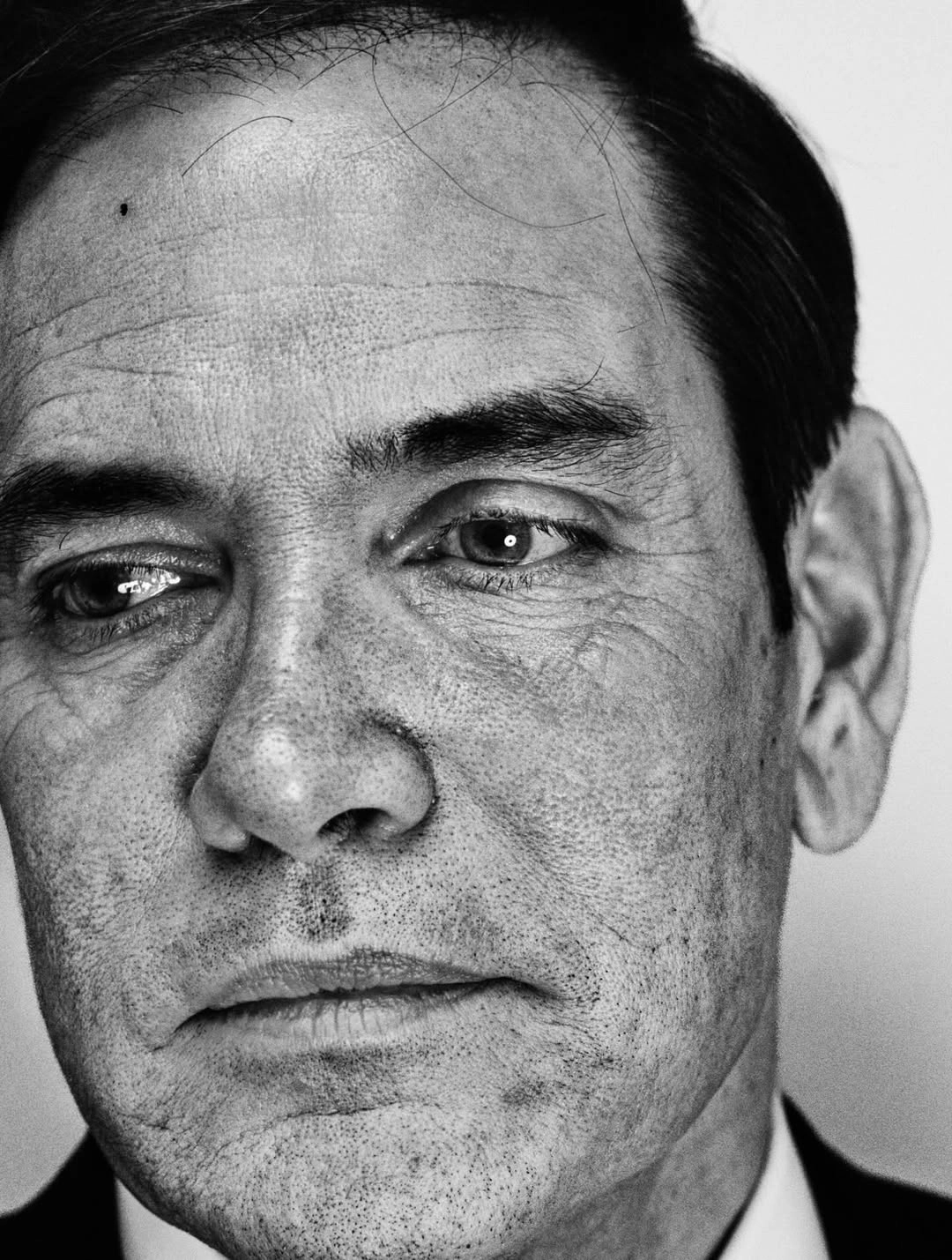

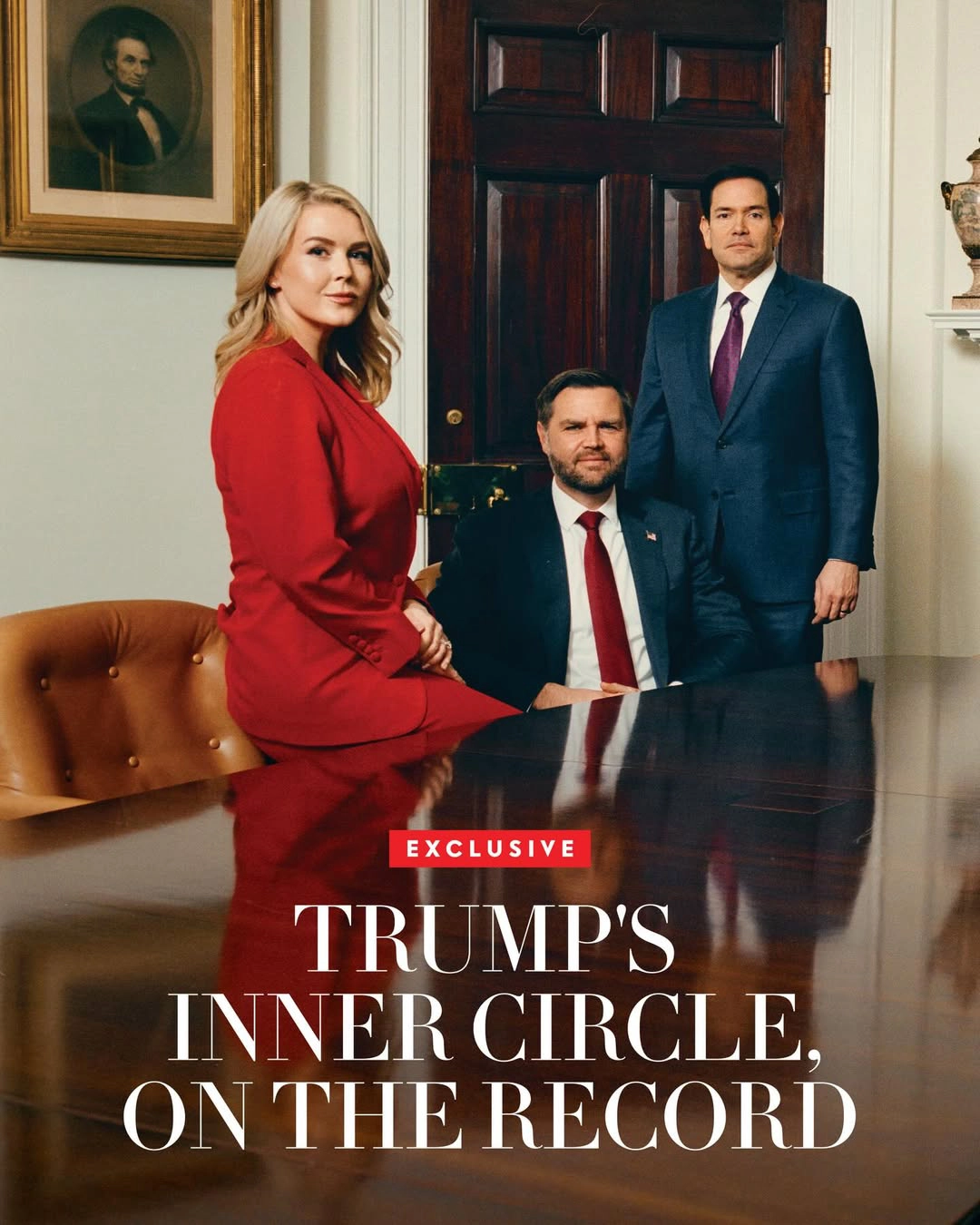

Marco Rubio. Image courtesy of Vanity Fair’s Instagram

Sargon of Akkad’s grandson was born hunchbacked. His grandfather had raised the first known empire, anchored in the lands of ancient Mesopotamia. He was fond of the boy, and let him do whatever he pleased. When he strode peacock-proud through the palace corridors, the servants—because of his short stature—bowed as he passed. And so his most recurrent vision became an endless rosary of crowns: some hairy, others smooth and shining. It gave him an utterly distorted view of life. Today’s grandchildren are not all that different.

Naram-Sin of Akkad—as the child was named at birth, in 2254 before Christ—was the first person to proclaim himself a god while still alive, ignoring the almost healthy tradition of kings who merely mediated with the divine. This unrestrained self-assertion, unprecedented in its time, would be fixed in the Victory Stele, where he appears wearing a horned helmet—an attribute reserved for deities—dominating his enemies from an elevated position: his favorite one.

Although his image did not pursue physical realism—perhaps beyond the reach of the artists of his time—it nonetheless fixes him as a recognizable historical individual and marks one of the earliest known examples of political portraiture in history.

The pharaohs who came later would take self-representation to a superhuman, openly ostentatious scale. It would take a long time before the person who governs and decides the fate of many would be regarded as “royalty.” For countless years, they promoted the art of portraiture—almost always with open eyes, staring directly at the viewer, who would thus feel watched and permanently under control, amen. It was also a deliberate act of adulation. Many painters—the most prominent of each era—were more than willing to serve power. Their task was to beautify it, idealize it, disguise its flaws, and ultimately construct an image of authority beyond all doubt.

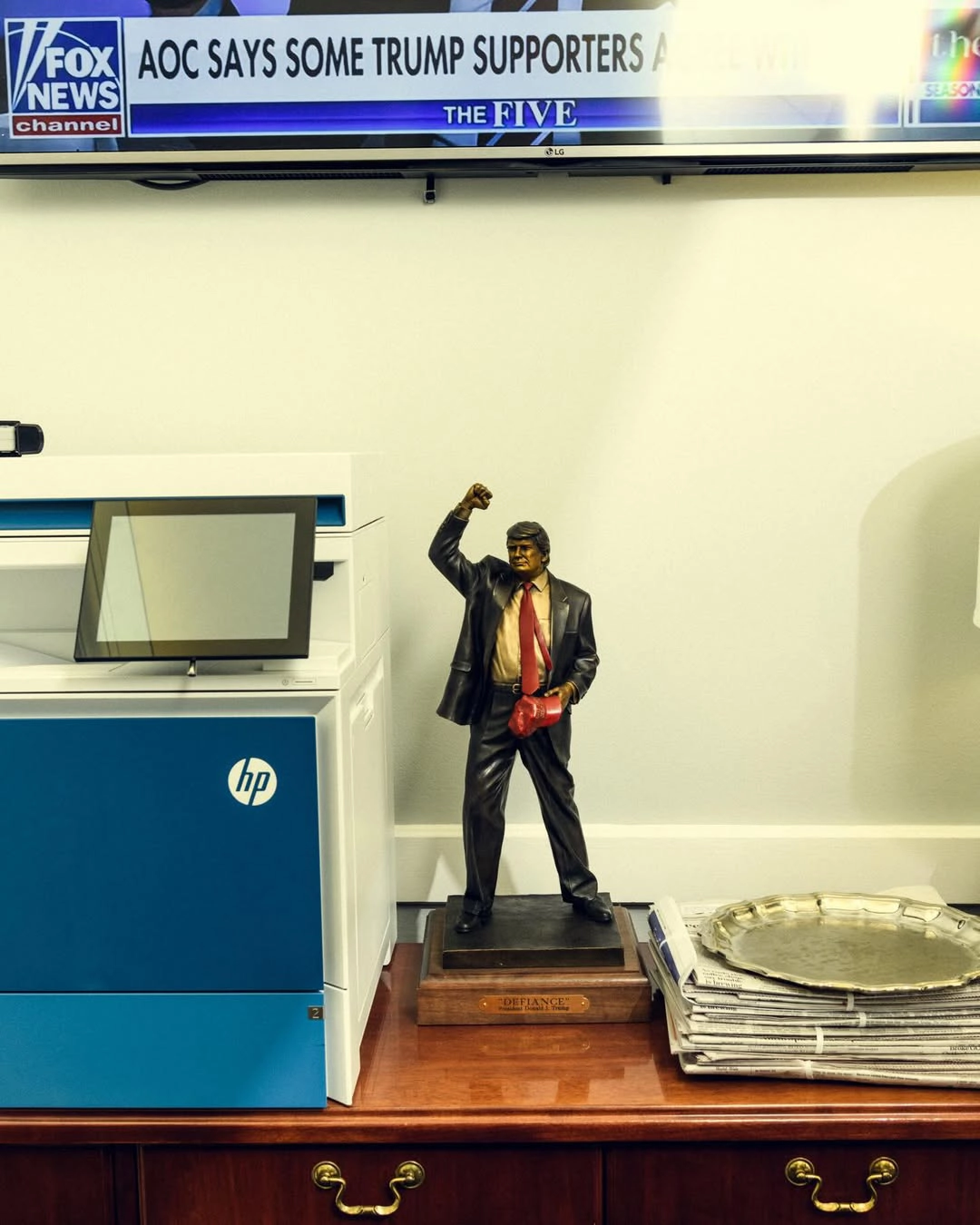

Almost four thousand years after the deliriums of Naram-Sin of Akkad, by the late nineteenth century—photography already invented—and even into the twentieth, portraiture ceased to be a mere instrument of legitimization. All orders wobbled after the First World War. Empires fell; the figure of the heroic ruler lost credibility. Photography—since painting was, at that moment, in decline—began to show leaders as tired, human, and fragile. Leaders in disgrace looked more disgraced than ever before, and by the end of the century portraiture had become a form of public interrogation, at least in countries with a free press. In totalitarian regimes—the Soviet, the Chinese, especially North Korea, and on this side of the world, the Caribbean—the same two- and three-dimensional exaltation once fashionable in the Egypt of the pharaohs and in the Mesopotamia of the divine grandson has been practiced with relish and urgency.

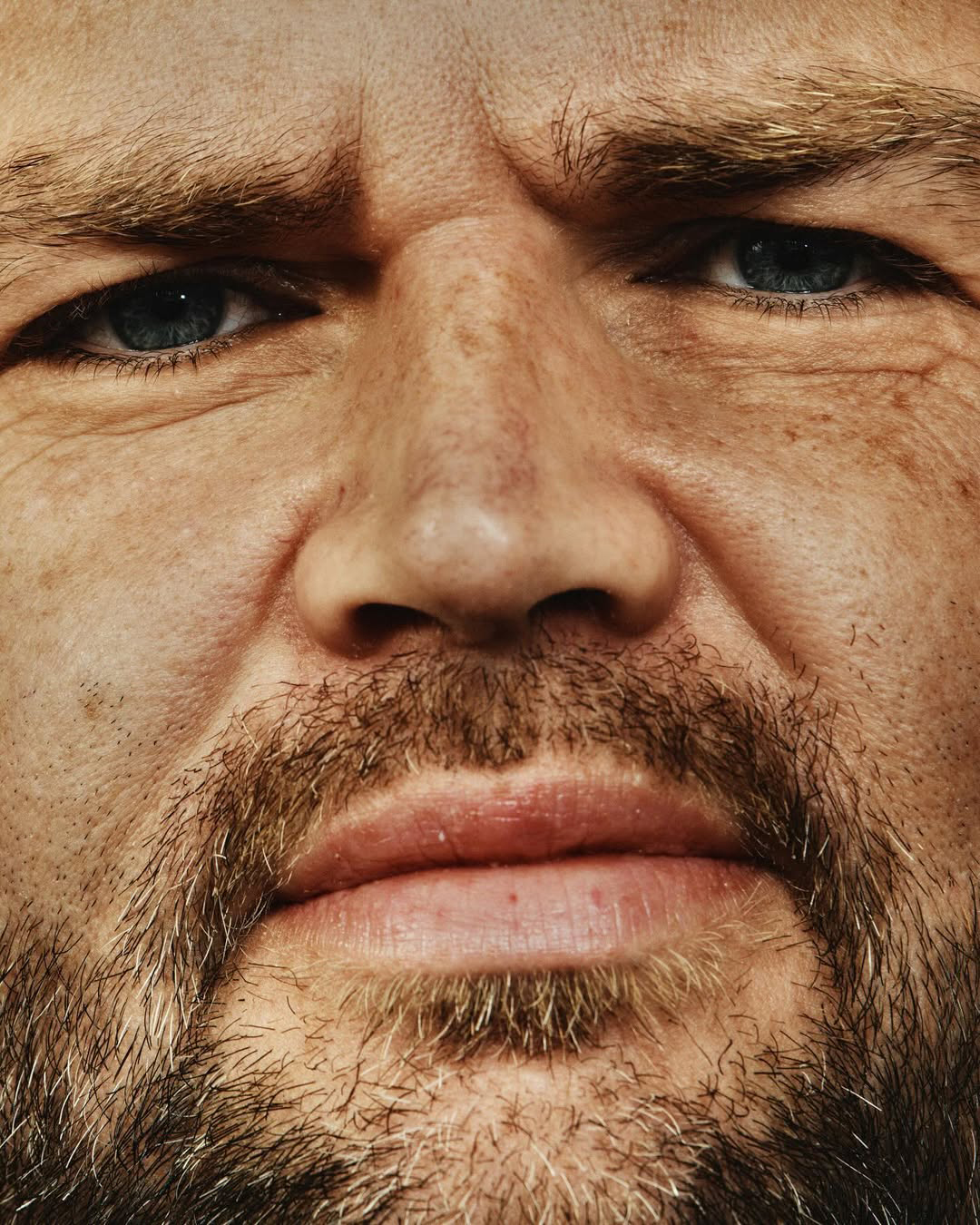

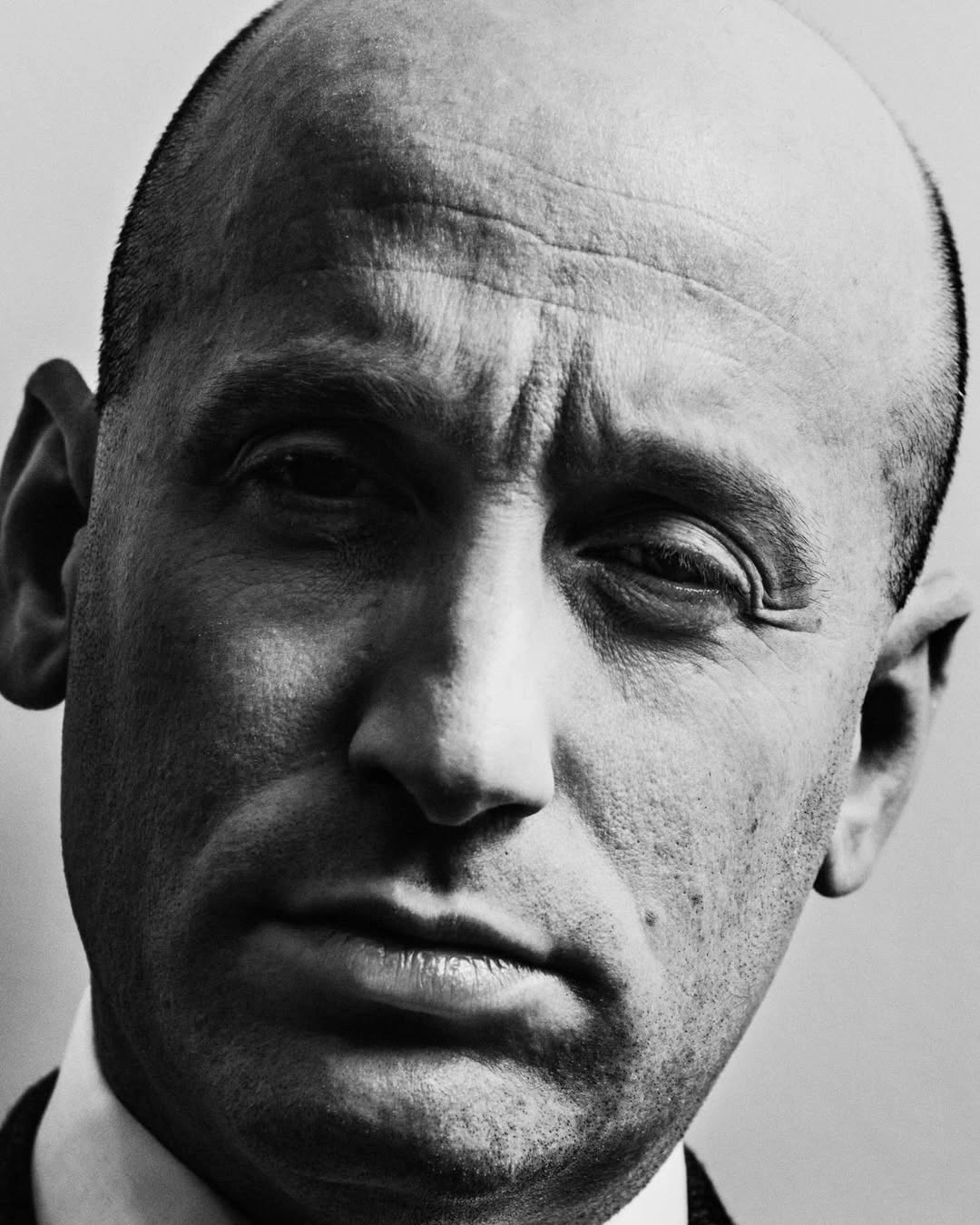

Probably due to lack of information, visual culture, or formal training, I had never seen a photographic session like the one Christopher Anderson carried out for Vanity Fair. It is a photographic record of the senior ranks of the current president of the United States—who, incidentally, is not included. I can’t help thinking of a saying from my homeland: play with the chain, but don’t touch the monkey. The photographs were published on December 16, illustrating an article by Chris Whipple. As expected, they did not go unnoticed and provoked an immediate and intense reaction on social media.

Because let’s be clear: these are not neutral portraits, much less flattering ones. They were conceived within a harsh, raw, and unforgiving aesthetic. Brutalist would be my definition. The protagonists’ faces reflect tension and discomfort. The framing was read on social media as deliberately hostile. The lighting—implacable, clinical, almost surgical—magnified the damage that exposure inflicts on human skin, on everyone’s skin. The norm is to respect certain codes, apply a filter, mercifully retouch reality.

But mercy has no place here. The “high authorities” we see daily in the media—rugged, imposing—reverberate in Vanity Fair like elderly figures forgotten in the sun, abruptly awakened from a weeks-long sleep. They may function as metaphors for political double talk, for exhaustion. In Marco Rubio’s case, the image looks like a medical photograph taken under polarized light to assess dermatological damage. The ironies circulating on social media focused on an alleged loss of integrity or signs of decay.

What was Vanity Fair aiming for? Because it was not Anderson’s idea, of course. To document power? To turn it into spectacle? An unexpected contribution to the Résistance? Politically, nothing will happen. In the circus we inhabit, the clown is killed every night. Symbolically, however… the images went viral and will likely cement one of the narratives of “Trump 2.0.” They will reinforce some of the dominant adversarial currents. They present the elite as foot soldiers of a dark, aggressive government—operatives who, under the right light, can be exposed and judged by the tribunal of art.

Returning to a not-so-distant past. In 1990—perhaps 1991—a Bulgarian student was expelled from ISDI—the Higher Institute of Design—after a lightning meeting in which we voted for and against her. She had copied a caricature of Fidel Castro turning into a pig from a magazine kept in the Information Center, the school library. A student with a heart blacker than coal—Elio, I don’t remember his last name—pulled the drawing from her wallet and went upstairs to report her.

She was expelled by an overwhelming majority, close to sixty or seventy students. Only three voted against it. If memory serves, Diocelis, Pedro Juan Abreu, and “El Negativo.” I voted in favor because I knew her fate had already been sealed, also out of cowardice, and because my dignity was tender, pale, and weak-rooted. My friend Diocelis was sitting to my right; he was the first to vote against it. When he raised his hand—and himself—to refuse, my dignity fell to the ground and shattered. I have spent decades painstakingly restoring it.

People like Anderson, like the executives at Vanity Fair, like many of my friends, have my full respect.

P.S.

A couple of comments I found on X:

—Marco, honey, exfoliate.

—Why does he look like someone just killed his dog 😭?

If you’re a regular reader of this blog and enjoy its content, you might consider contributing to its upkeep. Any amount, no matter how small, will be warmly appreciated

Founded in 2021, Echoes (Notes of Visual Narrative) invites everyone to explore together the visual codes that shape our world—art, photography, design, and advertising in dialogue with society.

Copyright © 2025 r10studio.com. All Rights Reserved. Website Powered by r10studio.com

Cincinnati, Ohio

Comments powered by Talkyard.