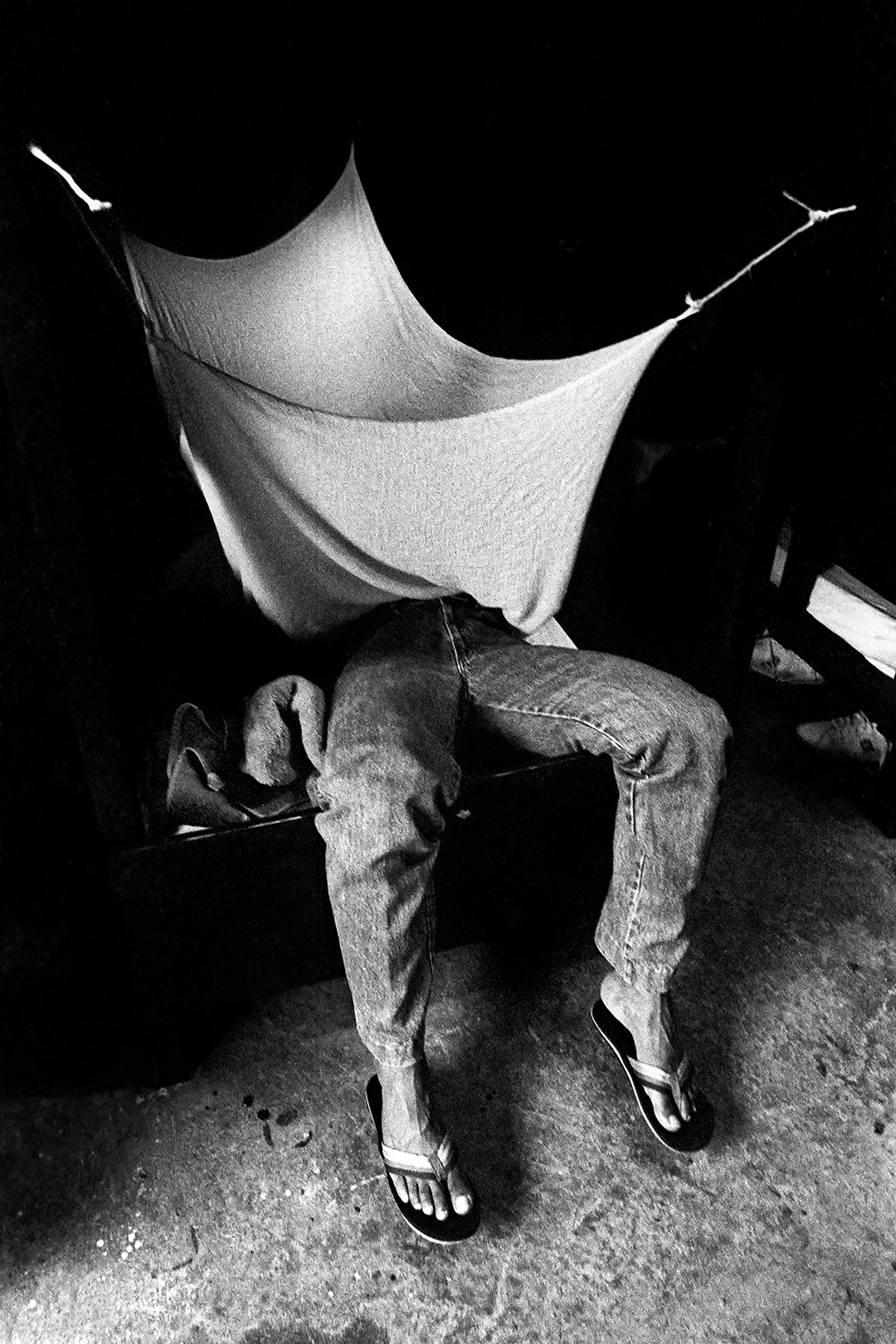

From the book Documentos personales; Untitled, 1989

Gelatin silver print

Image (at open): 6 × 8¾ in. (15 × 22.3 cm)

Sheet (at open): 6 × 8¾ in. (15 × 22.3 cm)

The Madeleine P. Plonsker Collection, Gift of Madeleine and Harvey Plonsker

Object number 2024.112

In his dialogue with reality—understood as an expansive living nature, and therefore never still before the artist’s pretensions—Pedro Abascal, who requires the road as much as the camera for his vital labor, has come to discover the possibility of drawing through the lens.

When I was a child, we lived in Santa Isabel, one of my grandfather’s farms. We were surrounded by trees, animals, and ravines. At that time, I did not know how to measure distance in kilometers, but the nearest house was so far away that one could grow weary walking to it. Unless it was through a battery-powered radio, neither my parents, nor my siblings, nor I could easily speak with anyone outside the family. That is why we valued visits so deeply—even those from strangers.

One afternoon, Leonardo arrived. At the time, we neither knew his name nor the purpose of his visit. He asked permission to dismount from his skinny beast and step onto the porch. After drinking two glasses of water, he said tersely: I am a photographer, and I travel through the region taking pictures for anyone who is interested. I had, of course, seen photographs before, but I had never stood before a photographer. I believed then that he must be some sort of magician—because otherwise, how could he leave someone, or a moment of someone, fixed onto paper?

My mother dressed us in our finest clothes, combed our hair, powdered us, even dabbed us with perfume, while Leonardo returned to his beast and brought back a pair of deep saddlebags. Seated on a broad stool, he removed a device we did not recognize. An old Kodak 120 camera, which would later become, in our eyes, the fundamental apparatus of his magic. He placed us tightly together, one beside the other, looked at us through the device, and a dry click was heard. That’s it, he warned us. What we did not like was learning that the photographs would be delivered the following week; we had assumed they would appear instantly, like the oft-mentioned rabbit pulled from a hat.

Anxieties aside, the man returned, and indeed, there we were—wearing the clothes of that day, with the ravine and a strip of brush behind us, our faces governed by smiles and bewilderment. After that, Leonardo returned frequently, and as there was little money, my mother sometimes paid him with eggs or chickens. Many years have passed, and the photographer has never ceased to strike me as special and enigmatic—someone who suddenly hands us fragments of our own lives and, more often than not, draws our attention back to ourselves.

For days now, I have been looking through, entering and exiting the personal documents of Pedro Abascal, and increasingly I recover that childhood wonder with which I witnessed the first photograph Leonardo took of us. From that wonder, I strive to uncover the keys to Abascal’s art—which is not magic, but the conjunction of accumulated wisdom and the gifts bestowed upon him by his gods.

Just a handful of photographs, drawn from the immense number Abascal has taken over the course of a decade. Perhaps those that have best served him in offering a spiritual portrait of himself. Images that always reveal him in motion through Havana—that powerful character—constantly vibrating through its objects and its people. Man and camera as an indispensable additional limb, passing as if by chance, arriving suddenly, entering unannounced, in order to find the human being within the daily ordeal of living and to leave them inscribed within the territory of dignity.

Abascal manages to capture the unreal appearance of the everyday, or to make us understand that in the succession of one day after another, habitual human actions and familiar settings can assume an expressionist projection that reveals their essential meaning.

The photographer has taken his profession as a way of life, and does not concern himself with endlessly stuffing his satchel with strange faces and bodies merely for the pleasure of hoarding the unknown. Through the successive neighbors who make up the body of his personal documents, Abascal has assembled the puzzle of his past years, his present hustle, and the unforeseeable to come—without omitting the final tram stop. The place where we all disembark, definitively silent in the depths. Yet without attempting to seize his chance harvest, one must point out what he surely already knows: these same photographs, through their rich attachment to reality, also function as a proposition—inviting anyone who looks at them to know themselves a little better.

Untitled, 1991. Gelatin silver print, 8 × 5½ in. Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund (2022.486). © Pedro Abascal

In his dialogue with reality—again, as an expansive living nature and therefore not still before the artist’s claims—Abascal, who needs the road as much as the camera for his vital labor, has discovered the possibility of drawing through the lens. Of striking, at the exact moment, the temptation of the inevitably photographable, and resolving it through compositions animated by a savory dynamic of vertical and horizontal lines, and suddenly curves… by means of which the sensation of movement emerges.

In this kind of cantata that Personal Documents constitutes, each photograph—without losing its aesthetic individuality—forms part of the greater meaning the book offers. For that reason, I have struggled against the temptation to single out certain images. And yet, I have succumbed to it, aware that the polysemic character of these images will allow others to choose different ones, or to coincide with me only partially.

For my part, I now keep among the finest ingredients for sensory pleasure that pair of elderly friends, retelling their lives to one another in a bar built especially for them. Or that old man seated beside his door, sharpening his gaze so that the inevitable does not catch him unprepared. The worker hardened by time and labor, displaying on his chest the tattoos of Che and the hammer and sickle, like two old medals brought back from war. Each day I converse with the skater—whom I wish I were—powerful and fragile, lifted into the air. That photograph born with antique tones, of the fisherman and his dog. I return immediately to the street’s commotion with that triptych of the camello: the man posing from the window as if within a picture frame, the fare collector at the door poorly disguising his indolence, and the woman with the child, her bristling profile. That man falling like a Christ among his people. Or that startled woman, so overwhelmed by the anticipation of flavor from foods that only survive in the lime of the walls. That strange woman, dead from pleasure or dead on Monserrate Street. The patient sorter of rice, as if awaiting fortune’s definitive blow. The shop where the image-maker blends with music brought from India and whatever is unfolding just outside on the street. These men, like myself, reading in the smallest newspaper the fate that awaits us. The father, perhaps warning the child of all that may happen beyond the shore. She with her back turned to everything, her face hidden in silence. And one must not look away, because suddenly, in the middle of a cemetery, the arrow and the ghost coincide—but when one imagines having that dead dove at one’s feet, the breath of war is immediately sensed. Fortunately, we are reassured by signs of respiration: the foreshortening of clothes hung out on a balcony, and the man with the double bass, who departs with his music elsewhere. The children on the poor swing provoke fear in me, and that rebellious angel on Villegas Street, with his careless beauty, hands me his dagger of hope…

Pedro Abascal offers us sufficient testimony to sustain the firm certainty that photography is the constant mirror.

Foreword to the book Personal Documents, by Pedro Abascal, presented on the afternoon of November 5 at the Fototeca of Cuba.

Bladimir Zamora Céspedes. Havana, Winter 1993

If you’re a regular reader of this blog and enjoy its content, you might consider contributing to its upkeep. Any amount, no matter how small, will be warmly appreciated

Founded in 2021, Echoes (Notes of Visual Narrative) invites everyone to explore together the visual codes that shape our world—art, photography, design, and advertising in dialogue with society.

Copyright © 2025 r10studio.com. All Rights Reserved. Website Powered by r10studio.com

Cincinnati, Ohio

Comments powered by Talkyard.