Pikene på broen (Girls on the Bridge), 1902. Oil on canvas, 101 × 102.5 cm (39 3/4 × 40 3/8 in.). Signed and dated E. Munch 1902 (upper right). Edvard Munch arranges a group of female figures along the diagonal axis of the bridge, whose linear structure organizes both spatial construction and psychological distance. The figures, aligned yet inwardly detached, do not interact with one another and appear suspended between physical proximity and emotional isolation. The landscape—water, sky, and shoreline—mirrors this affective reserve through simplified forms and active chromatic fields.

Edvard Munch was one of the most finely tuned loudspeakers of his time’s spirit—the Zeitgeist. Dostoyevsky had been one before him, and Kafka would be another later on. He belonged to that rare class of human beings God seems to have assembled in haste—leaving the skull half-finished, the sutures open, the nerves exposed—those daemons of History chosen to transmit its message to humanity.

He was also profoundly unfortunate. “You paint like a pig, Edvard!” shouted Gustav Wentzel in 1886, a young academic painter, at the exhibition in Kristiania (today’s Oslo) where Munch showed The Sick Child. “You should be ashamed of yourself, Edvard!”

The original version of Det syke barn (The Sick Child), painted between 1885 and 1886 by Edvard Munch, is held at the Nasjonalgalleriet in Oslo and constitutes one of the foundational works of his early pictorial language.

At the time, Munch did not have a penny. His closest friends were nihilists. The rest were alchemists, sadists, demonolaters, absinthe addicts, and, at moments, deeply disturbed playwrights. Ibsen visited his 1895 exhibition—the one that ignited a public debate over the artist’s sanity. It is said that he warned him, with a cavernous grunt: “The more enemies you have, the more friends you will gain.” The addressee, failing to understand, chose to ignore him. Another writer and dramatist, Strindberg—a fairly unhinged paranoiac—wrote to his publisher: “As for Munch, he is now my enemy… I am certain he will not miss an opportunity to stab me with a poisoned knife.” Years later, when a gust of wind knocked over his easel on the beach, Munch did not hesitate to charge Strindberg with the offense.

The death of God, alienation, the self as the destabilizing center of experience: this was the daemon’s message. The complete and devastating gospel of modernity lived in Edvard Munch’s entrails. It forced its way through his flesh and fibers and burst, mutely, in the gelatin of his Scandinavian eye sockets. These certainties triggered several nervous breakdowns and a massive thirst for any distilled liquor. Curiously, such lack of control made him strangely attractive to women. He was hospitalized several times. He went hungry, he raved, he was vilified—and, like every great artist, he understood perfectly what was happening to him. “If only one could be merely the body through which today’s thoughts and feelings flow,” he wrote to a friend. “To perish as a person and yet survive as an individual entity—that is the ideal.”

What form can creation take after the fall? What is left to speak of? Not the merely external world, inert and dull. Nor the retinal shimmer sought by the Impressionists, whose practices he had encountered during his time in Paris. Munch did not want to go beyond his eyes, but deeper into his own head. He sought the deepest imprint of the exterior upon the interior: the pressure of the universe upon the mind. For him, that was reality.

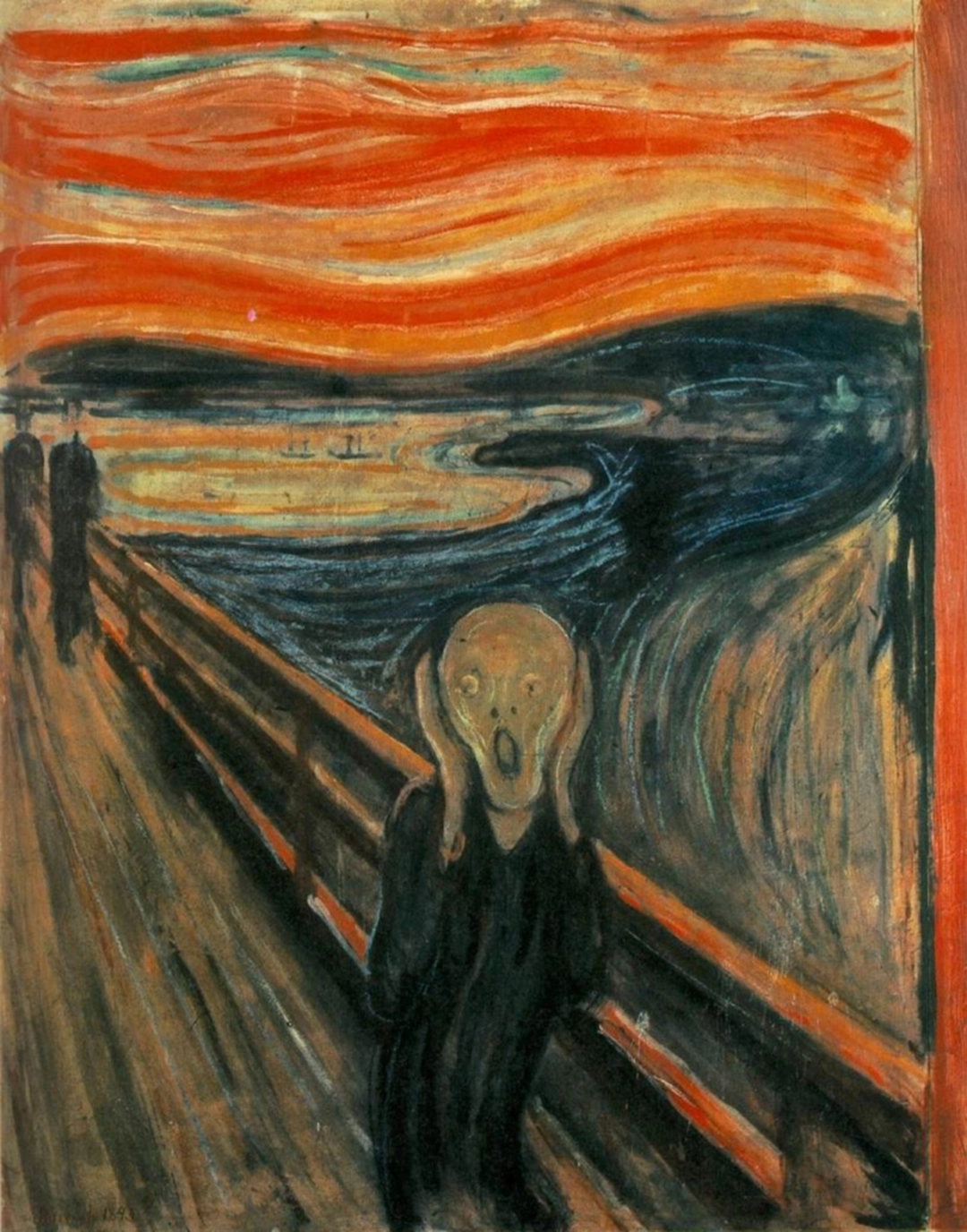

Skrik (The Scream), painted in 1893, executed in oil, tempera, and pastel on cardboard (91 × 73.5 cm). This is the original version of the motif, held at the Nasjonalgalleriet in Oslo.

Thus he arrived at his great success, his statement to the world: The Scream. The well-known figure in the foreground on the bridge, the head tilted like a lightbulb, the uncertain hands pressed to the ears, the acoustic bands in the sky distorting the sunset, the caricatured face disfigured by terror. Of the human, nothing remains but an open channel to the vibration of the real. Overwhelming—“I heard an extraordinary, bestial scream pass through nature,” he later wrote.

Trembling Earth, at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, was a splendid exhibition. It was not conceived as a refutation of The Scream, but it offered such a distinct angle that the habitual image of Munch suddenly felt painfully incomplete. Almost a revelation. Mystical experiences can be negative—as many of his undoubtedly were—but they can also show you what it feels like when the Holy Spirit turns its hands over and lets you fall. And as the Beatles once said: the deeper you fall, the higher you rise.

Den gule stammen (The Yellow Log), 1910; some sources extend the date range to 1909–1911, though 1910 is the most widely accepted. Oil on canvas, 94 × 124 cm. Collection of the Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design. The work does not belong to the Munch Museum but to the National Museum of Norway.

The selection of works formed a constellation of generous presences. Seen today through modern eyes, they radiate and spill a supernatural warmth. At the entrance to the gallery stood The Yellow Log. A group of felled trunks stacked in a snow-covered forest. The yellow log asserts itself as a projecting force, advancing toward the viewer and putting the pictorial space into crisis, as straight as a laser, like the railing in The Scream. Yet this log shines with a strange magnitude; it illuminates like a cauterized ray of sunlight, its end severed, transformed into a dazzling disc of white gold.

Slåttekar (The Haymaker), 1917. Oil on canvas, 130 × 151 cm. Collection MUNCH – The Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway (inv. MM.M.00387). Edvard Munch presents a solitary haymaker in the midst of labor. His body divides the composition into two halves. Yet he neither dominates the landscape nor integrates with it peacefully. He is inscribed within a pictorial matter governed by movement, and his physical effort dissolves into the visual structure.

In The Haymaker, the landscape tips forward like a mass in motion, a sustained summer outpouring that threatens to sweep away the figure occupying the foreground. But the haymaker—through the brief flexion of his legs, the firmness of his stance, and the restrained torsion of his body as he calmly swings the scythe—redirects the current and keeps it flowing. The field is his home.

Champ de choux (Cabbage Field), painted by Munch in 1915. The work is held at the Munch Museum and measures 67 × 90 cm. The composition and palette evoke both the beauty and the harshness of nature.

And those bluish-green rows of cabbages, steaming, in Cabbage Field… do they move toward the horizon, narrowing into an omega-point, a lightning strike of nullity? Or do they surge outward from it, rushing toward us? “Embraced by cabbages”—that is how some visitors said the exhibition made them feel.

Solen (The Sun), 1911. Oil on canvas, 455 × 780 cm. Aula Magna, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. Edvard Munch places a frontal, expansive sun at the center of the composition, from which chromatic rays radiate outward, organizing the landscape into successive layers. The scene articulates an abstract dawn whose force dominates the space and reconfigures it entirely. The landscape is subordinated to this luminous energy, while the rhythm and directional flow of movement dissolve the stability of the horizon. The visual field of tension that emanates from the core of the painting constructs a vision of light that operates not as an atmospheric effect, but as a structural principle.

That melancholic, mad, somber Munch—mutilated by modernity—was well represented in Trembling Earth. He emerges in the unsettling scenes in forest clearings, in vacant faces and heads cradled by weak hands, in semi-allegorical, desolate figures gazing out to sea, in apple trees boiling in a toxic soup, and in a black-and-white lithograph of The Scream. But all these images function as a counterpoint to the exhibition’s core. One wall away from the lithograph of The Scream hangs The Sun (1910): a violent discharge of rays and light hurled from an oceanic dawn. Behind all that radiance, one can even discern the vague cranial outline of The Scream’s head, as if the sun itself were the explosion of a third eye.

Munch held a peculiar metaphysics. An intuitive—vaguely scientific—faith in the self-renewal of existential ferment, in the compost of crushed souls, recycled through infinite cycles. He would later explore this personal mythology in images of extreme luminosity. Masculine and feminine essences; beings of volcanic longing. “The earth loved the air,” reads a crayon text on paper that he wrote on the cover of a 1930 album titled The Tree of Knowledge.

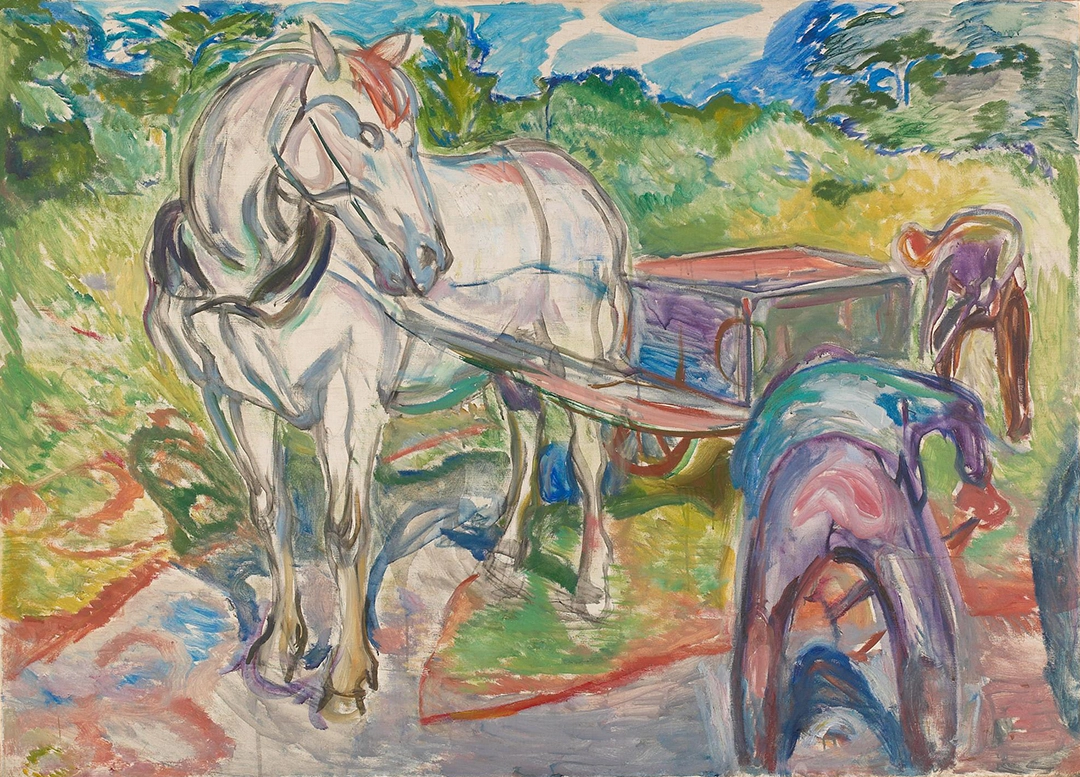

Gravende menn med hest og kjerre (Digging Men with Horse and Cart), 1920. Oil on canvas. Collection MUNCH – The Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway. Edvard Munch depicts a group of men engaged in working the land alongside a horse and cart, integrating physical labor into a composition structured by repeated gesture and bodily weight, where anecdote recedes in favor of a direct material presence.

Like every authentic craftsman, Munch respected work above all else. Forestry, harvesting, tilling the land. In Digging Men with Horse and Cart (1920), the men bend over their shovels while a white horse between the shafts resembles an almost transparent garland of muscle and taut energy. The horse—possibly modeled after Rousseau, Edvard’s own—nods toward the men who dig, invested with a gesture of near-ritual blessing.

Munch approached his own work with a remarkable lack of solemnity. Though he loved his paintings and referred to them as his “children,” he piled them carelessly, tripped over them, dripped on them, knocked them absentmindedly, or left them outdoors to fend for themselves against the elements. Half joking, half serious, he spoke of it all as a process of open-air curing, which he called hestekur—horse cure.

Someone visiting one of Munch’s late studios, upon asking why a certain canvas had a massive hole in one of its lower corners, was astonished to learn that one of the artist’s dogs had run straight through it.

His paintings—landscapes as much as depictions of human beings—are saturated with a deep passion. So said Goebbels. Hitler thought otherwise. In 1937, dozens of Munch’s paintings were ensnared in the Nazi roundup against “degenerate art.” Munch’s final years unfolded under German occupation, on his country estate in Ekely, Norway. On the day of his death, at the age of eighty, he was reading—once again—Dostoyevsky’s Demons.

Epletre i hagen på Ekely (Apple Tree in the Garden at Ekely), 1928–1929. Oil on canvas, 70.5 × 72 cm. Signed and dated lower right: Edv. Munch, omkring 1930. In this late work, Edvard Munch presents the apple tree from his Ekely garden as a form nearly dissolved into paint itself, where color and gesture displace description and the motif yields to the pressures of the pictorial field. Private collection.

The Scream will resonate until the end of time. It is cave painting on the inner walls of a human skull. Munch heard that scream, without question; it passed through his entire being. But there is a paradox. To produce an image like that—of such cosmic vulnerability—requires immense strength. You cannot collapse. Not completely. You must be extraordinarily resilient. You must be able to bear it. And Munch, for all his afflictions, could. He possessed a secret health, an inconceivable toughness, and this exhibition at the Clark put us back in contact with its sources.

NOTE

Edvard Munch was born on December 12, 1863, in Ådalsbruk, Løten, Norway, and died on January 23, 1944, in Oslo, Norway. He is buried at Vår Frelsers gravlund (also known as Vår Frelsers kirkegård) in Oslo, one of the country’s most important cemeteries, housing the graves of many central figures of Norwegian culture.

This text is a free re-creation of A Sunnier Edvard Munch. A New Exhibition Offers a Counterpoint to The Scream, an article by James Parker published in The Atlantic in September 2023.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog and enjoy its content, you might consider contributing to its upkeep. Any amount, no matter how small, will be warmly appreciated

Founded in 2021, Echoes (Notes of Visual Narrative) invites everyone to explore together the visual codes that shape our world—art, photography, design, and advertising in dialogue with society.

Copyright © 2025 r10studio.com. All Rights Reserved. Website Powered by r10studio.com

Cincinnati, Ohio

Comments powered by Talkyard.