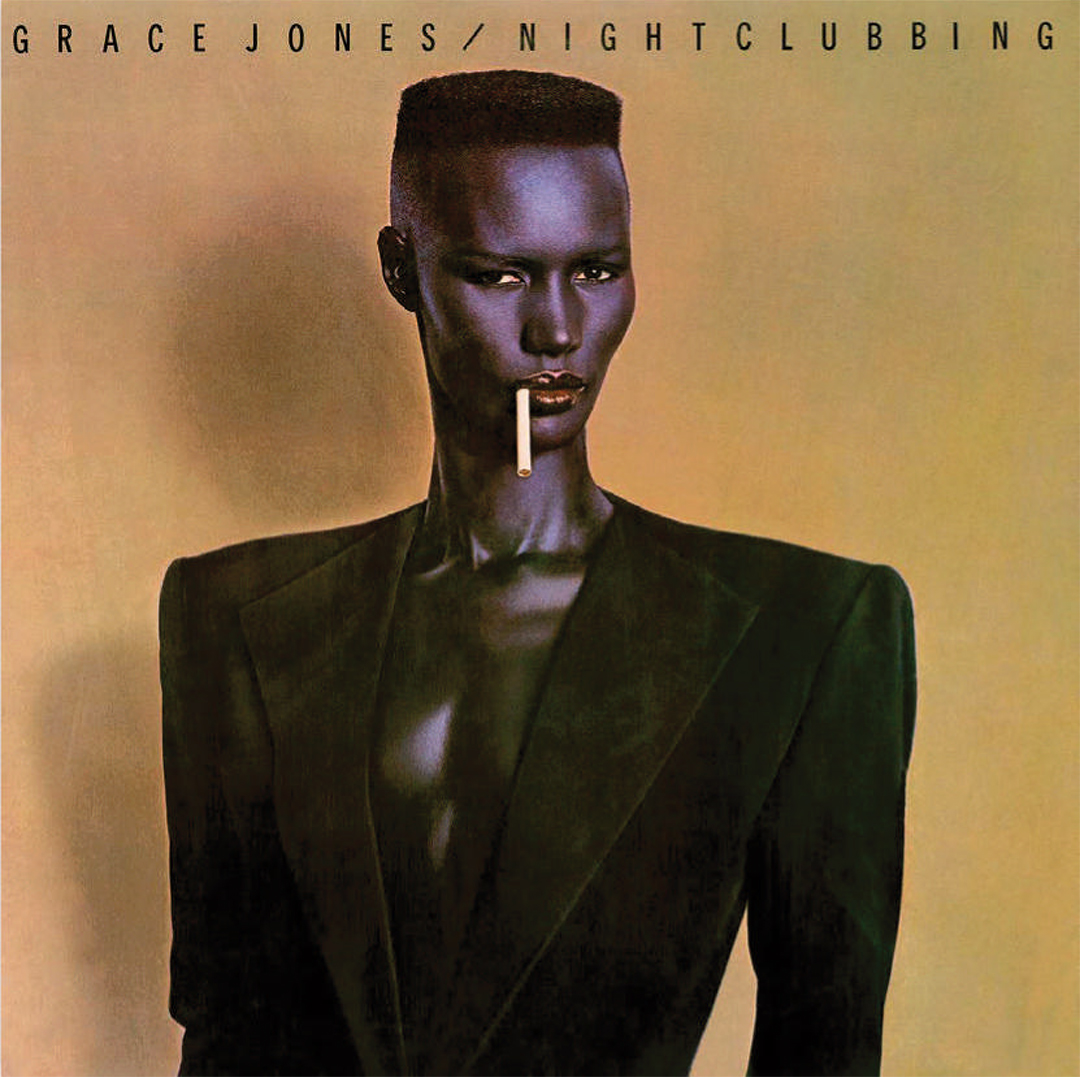

The epitome of androgynous cool, the effortlessly stylish cover of Nightclubbing helped to catapult singer Grace Jones to superstardom; the front cover featured Jean-Paul Goude’s painted photograph, Blue-Black in Black on Brown.

Netflix aired the final episode of Stranger Things on December 31, 2025. It coincided with the closing of an unusual and demoralizing year. A masterstroke. We will remember forever the day the Upside Down arc was sealed, Vecna definitively defeated, and Eleven’s story brought to a close—at every level: her power, and her life in the physical realm. The group of friends disperses as an active unit. Each takes a different path. And, above all, one of the warmest windows onto the extraordinary 1980s was shut.

Those years began with Reagan’s rise to power. His inauguration took place on January 20, 1981. In the offices of Granma, the Cuban state newspaper, the relentless clatter of typewriter keys never ceased: imperialism, Cold War, “hands off Central America,” “soil soaked in blood”… a rhetoric that, even today, remains intact.

In the United States, on August 1, Mark Goodman introduces MTV. With its first video, Video Killed the Radio Star by The Buggles, the industry begins to spin until it is completely overturned. Sound is no longer enough. A new layer must be added—vibrant, incandescent: the image. The record ceases to be merely musical and becomes an object that articulates multiple layers of meaning. Visual. Performative. An entire architecture of identity. In fact, vinyl reaches at this very moment its peak of aesthetic and iconographic sophistication. Without wishing to spoil the celebration, barely a year later, in 1982, Sony and Philips will bring the Compact Disc into circulation.

We are still in 1981. A 32-year-old Grace Jones releases her fifth studio album on May 11, Nightclubbing, under the Island Records label. It appears precisely at the threshold between the album as object and the artist as absolute visual icon. Much of this rests on the cover. Chris Blackwell, founder of the label and co-producer of the album, commissioned it directly from Jean-Paul Goude, who at that moment—at forty-one—was living his creative prime.

It was Blackwell who decided to take an existing photograph by Goude and turn it into the album’s official cover, crediting the work as “Cover painting by Jean Paul Goude.” The decision meant betting on a radical image that broke with the dominant disco iconography, despite internal resistance from the label’s A&R (Artists and Repertoire) department.

The cover of Nightclubbing went on to establish itself as one of the most influential images of late twentieth-century visual culture—not only because of its immediate impact, but because it redefined the relationship between music, identity, and iconographic construction.

The image ceases to illustrate sound. The “acoustic” image—if the term makes any sense—is displaced by plastic form as the central instrument of meaning. In a single gesture it condenses aesthetics, attitude, and cultural position. Grace Jones’s figure sustains a field of signification deliberately constructed to operate within ambiguity, generating—through tension and a defiant, sovereign pose—a transcendent presence.

‘Blue-Black in Black on Brown’, painted photo, New York, 1981

Jean-Paul’s image is not pure photography, but a photograph intervened with paint (painted photograph), titled Blue-Black in Black on Brown, produced that same year. Blue pigments were manually applied to the body to accentuate volume and structure. In a meticulous exercise in bodily geometry, shoulders were extended and head and silhouette stylized through hand painting, physical cutting of images, and artisanal recomposition—procedures proper to the plastic arts, not to documentary photography. A full decade before the release of Adobe Photoshop 1.0.

The result is an image that is sculptural, almost architectural. The body as concept. An operation that turns androgyny into active force, into a public figure resistant to any univocal reading. Its iconic character is further reinforced by a radical economy of means: no distractions, no texts or auxiliary images to soften its confrontational frontality. This is what there is. The viewer must resolve their discomfort, confusion, or attraction without the help of mitigating readings. A strategy that, at the time, generated doubts even within the industry ultimately proved that visual risk could be converted into symbolic capital.

Over time, the Nightclubbing cover has transcended its condition as a musical artifact to become fully integrated into the history of contemporary image-making. Its relevance has nothing to do with nostalgia or cultural fetishism. Any professional could sell this cover today. Any company would buy it. Its voice remains audible in current debates on gender and on the construction of the body as language.

If it landed on the cover of Vogue, I’d accept the trick—and thank them for it.

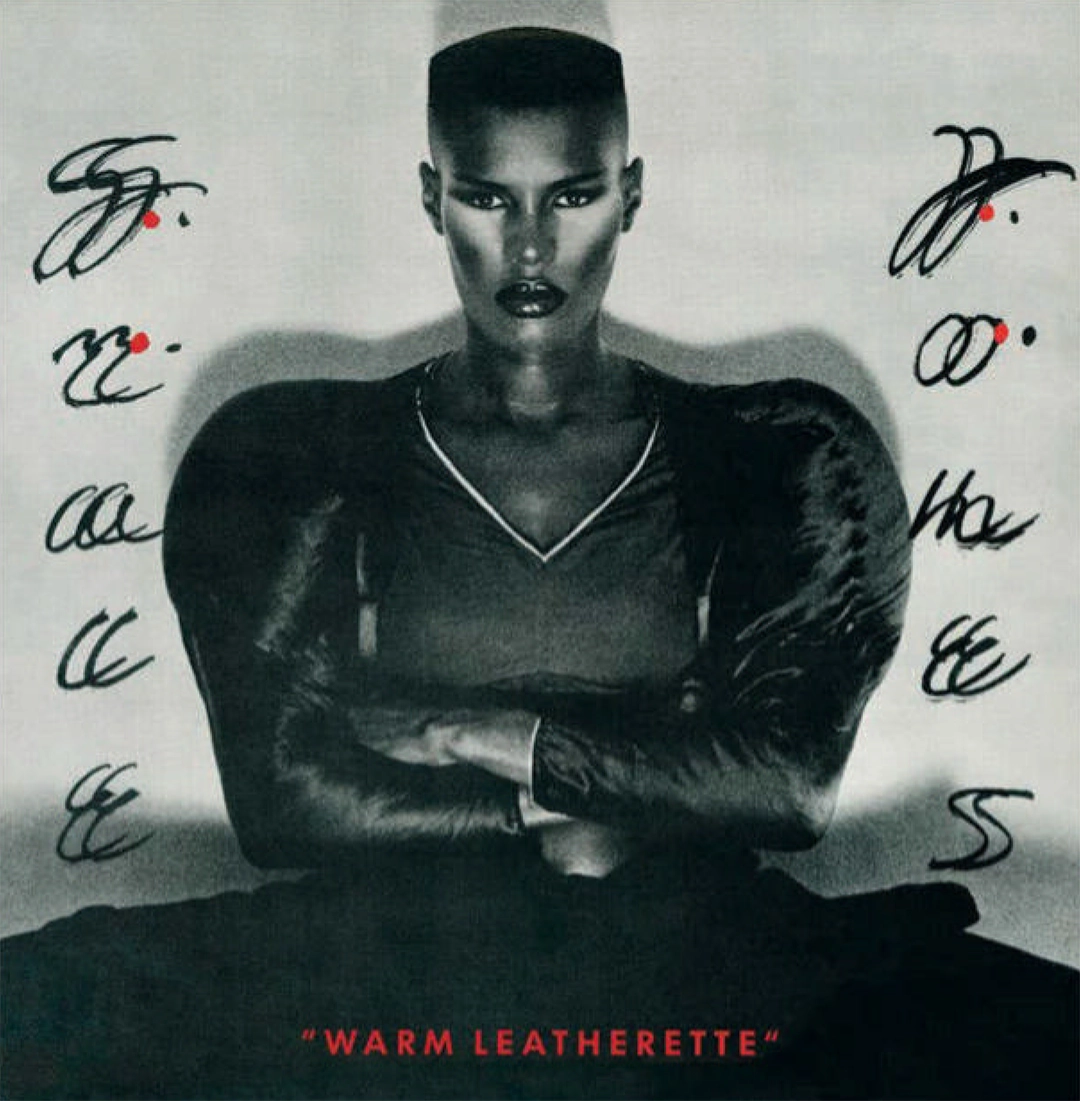

A bold image by Jean-Paul Goude graced the cover of the 1980 Grace Jones album Warm Leatherette

If you’re a regular reader of this blog and enjoy its content, you might consider contributing to its upkeep. Any amount, no matter how small, will be warmly appreciated

Founded in 2021, Echoes (Notes of Visual Narrative) invites everyone to explore together the visual codes that shape our world—art, photography, design, and advertising in dialogue with society.

Copyright © 2025 r10studio.com. All Rights Reserved. Website Powered by r10studio.com

Cincinnati, Ohio

Comments powered by Talkyard.