I don’t know Miguel Rodez personally. Nor does the immense—if small—majority who read this blog. It’s possible I crossed paths with him more than once at Miami openings over the last four years. Our relationship is, essentially, a social-media one.

For our regular readers, his name will likely be unfamiliar because he arrived in the United States in 1972, a thirteen-year-old adolescent. It was to be expected that Cuban art publications would overlook him—him and everyone else—especially through the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s.

Miami has never been easy for anyone. Not then, not now. The kind of success one can eke out in Cuba stretches for months; in Miami it lasts a fortnight. That’s the first reason you find so many artists who studied law, medicine, education—who, in their scant leisure, ground down by those “cheerful, vibrant, frenetic, and high-velocity” Florida workdays, still managed to push forward their personal projects.

There’s another circumstance I keep in mind: on this side of the straits, artists do not occupy the same rung in the food chain that they enjoy on the island. Not by a long shot. Which is why, a bit beyond the daily “every person for themselves,” artists occasionally feel real sympathy for one another—beyond the lifelong pull of tribal feeling. That’s not a data point; it’s the impression I carried away after four years working in an art institution in South Florida.

From those pioneer generations emerged dozens of artists who persisted and managed to build careers in an environment unimaginable to artists who studied in Cuba—constraints notwithstanding—and could devote all the time in the world to their professional development.

Rodez

I learned of him by chance, when I came across one of his photographs on Facebook and found it apt for a topic that was burning at the time. We became virtual friends, and since then he’s appeared frequently on my feed. I began to follow him; I even made a file for him among South Florida artists to keep track of his work and projects.

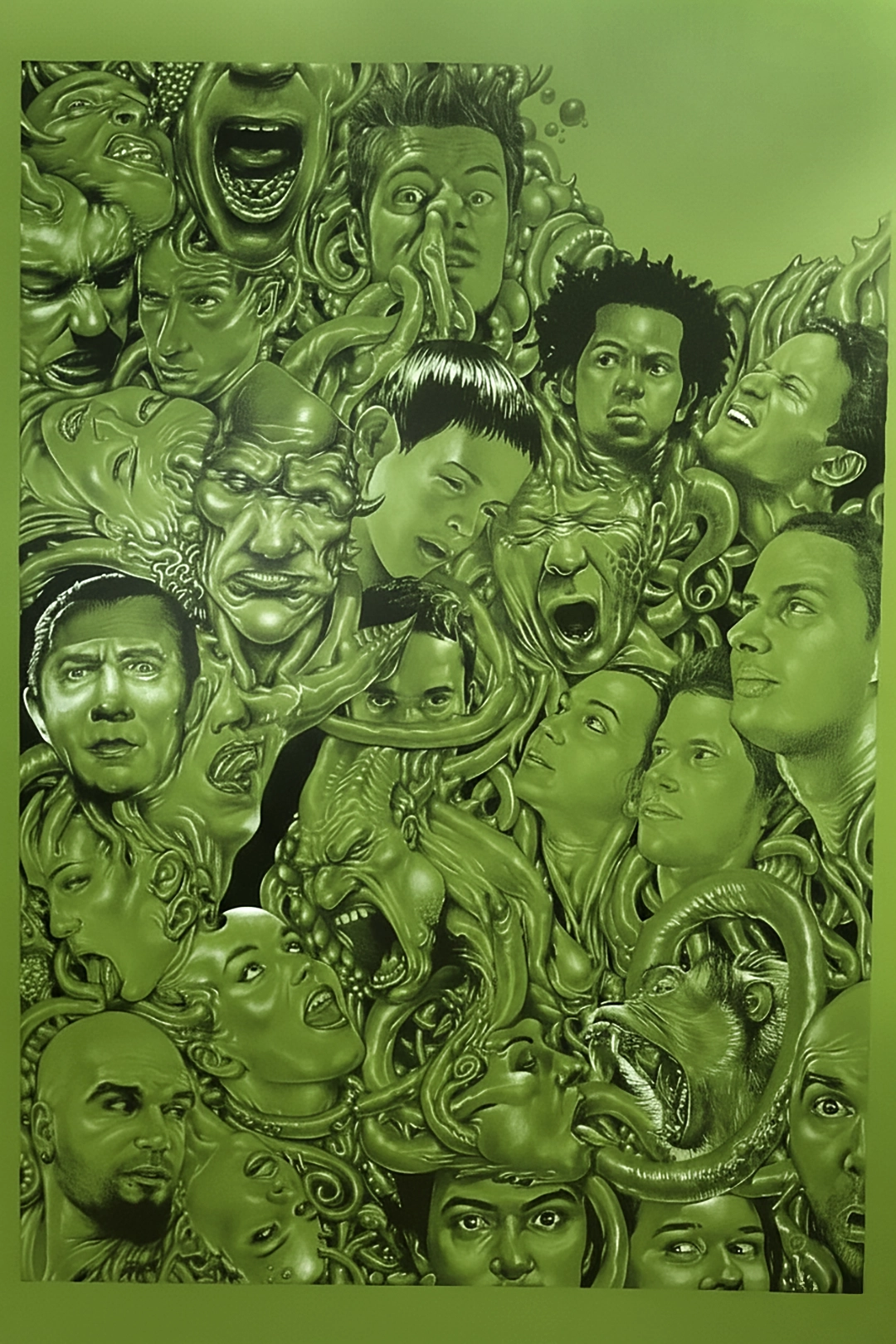

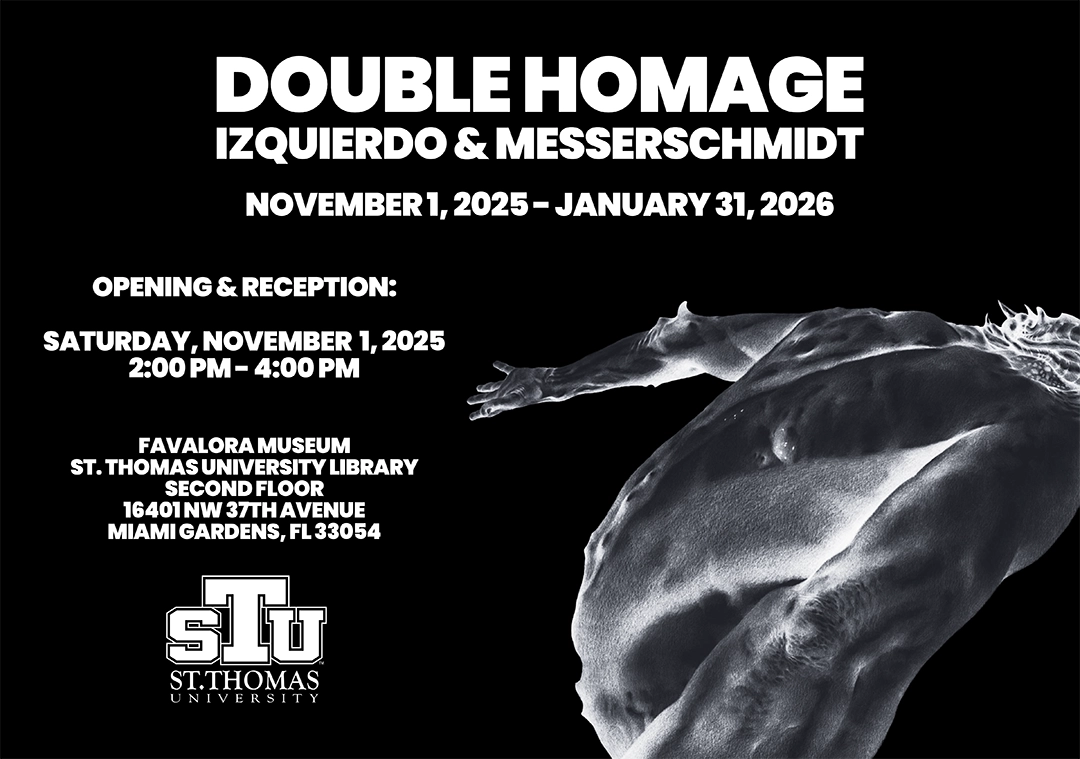

Double Homage is the most recent—an homage to the artists Frank Izquierdo and Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. Though two centuries separate them—Franz died in August 1783—they share the intention to probe the human soul through portraiture, via extreme facial or bodily expressions. Izquierdo also passed away, a victim of COVID, in 2021.

Miguel tells me he met him around 2010 at Jerry’s Artarama, an art-supply store in Miami. He worked there. Which means I likely saw him more than once, since I bought my paints there for many years. What struck Miguel was his character, his readiness to help. Frank answered his questions precisely, almost tenderly, with that rare talent for guiding without imposing. He later learned that, in addition to tending the store, he was also a visual artist.

He invited him to a show in September 2012—at the opening of his studio/gallery—with a selection of drawings. He got to know him little by little, and he tells me that what moved him most—beyond technical skill, for he was self-taught—was his human quality. We’ve all seen too often how talent arrives arm in arm with arrogance. Frank, he tells me, was a child hidden in an adult’s body. From there he dealt with the world, as if it were a game.

Frank Izquierdo. Self Portrait. January 21st, 2013

As curator and juror, Miguel was able to award him a prize in a competition and exhibit his work in several shows. One of them, devoted to self-portraits, left a mark on him. He visited Frank in his apartment and asked for a piece that would converse with two prior self-portraits. What emerged was one of the most interesting and accomplished self-portraits I’ve ever seen. Frank, self-portraying, widens the frame and summons his world—his colleagues from Jerry’s, friends, the film figures who pushed him to draw. With a strange sensuality he doubled his own face in the lower corners of the picture. The piece fixed a temperament: the portrait as an archive of the affective.

Frank Izquierdo and Elsita Lastres. Photo by Sergio Lastres.

On December 20, 2021, the news arrived that Frank had died. Rodez knew of a large body of work that remained unpublished. Two years later, at a memorial gathering, he asked those close to him to see Frank’s last pieces. That self-portrait had multiplied into several testimonies to a brief yet keenly used life. He decided the ensemble deserved to be shared and secured the place and the moment. It will open at the Favarola Museum at St. Thomas University in Miami on November 1.

Rodez will stage his homage with the series in which Frank makes his own to Franz Messerschmidt. Layers of recognition superimposed.

No one knows anyone in full. To pay homage is a human act that tries to stave off two abysses: oblivion and the destruction of the evidences of a life once it loses owner and custodian. In this case, a life that sought to replicate itself in works of art. It recognizes a character, an ethic of work, gentleness—a sensitivity that tried to traverse two centuries in a there-and-back journey. And it is also a closing that leaves the door ajar.

This exhibition—unlikely to be reviewed by The New York Times—is, like those that are, a testimony to a relational gaze, where all involved find themselves reflected. I believe that Izquierdo and Rodez, and Messerschmidt with his extreme grimaces, all recognize that the truth of a face lies in what overflows it.

I join the homage—to Rodez’s gesture, to the brief useful life of Franz Izquierdo, to the unhinged force of the German sculptor. Above all, I pay homage to all of us who emigrated and brought our dreams along with the passport. Dreams we shake awake when we think them dead; dreams we keep watch over, lest one day we find ourselves with two spare hours to make them real.

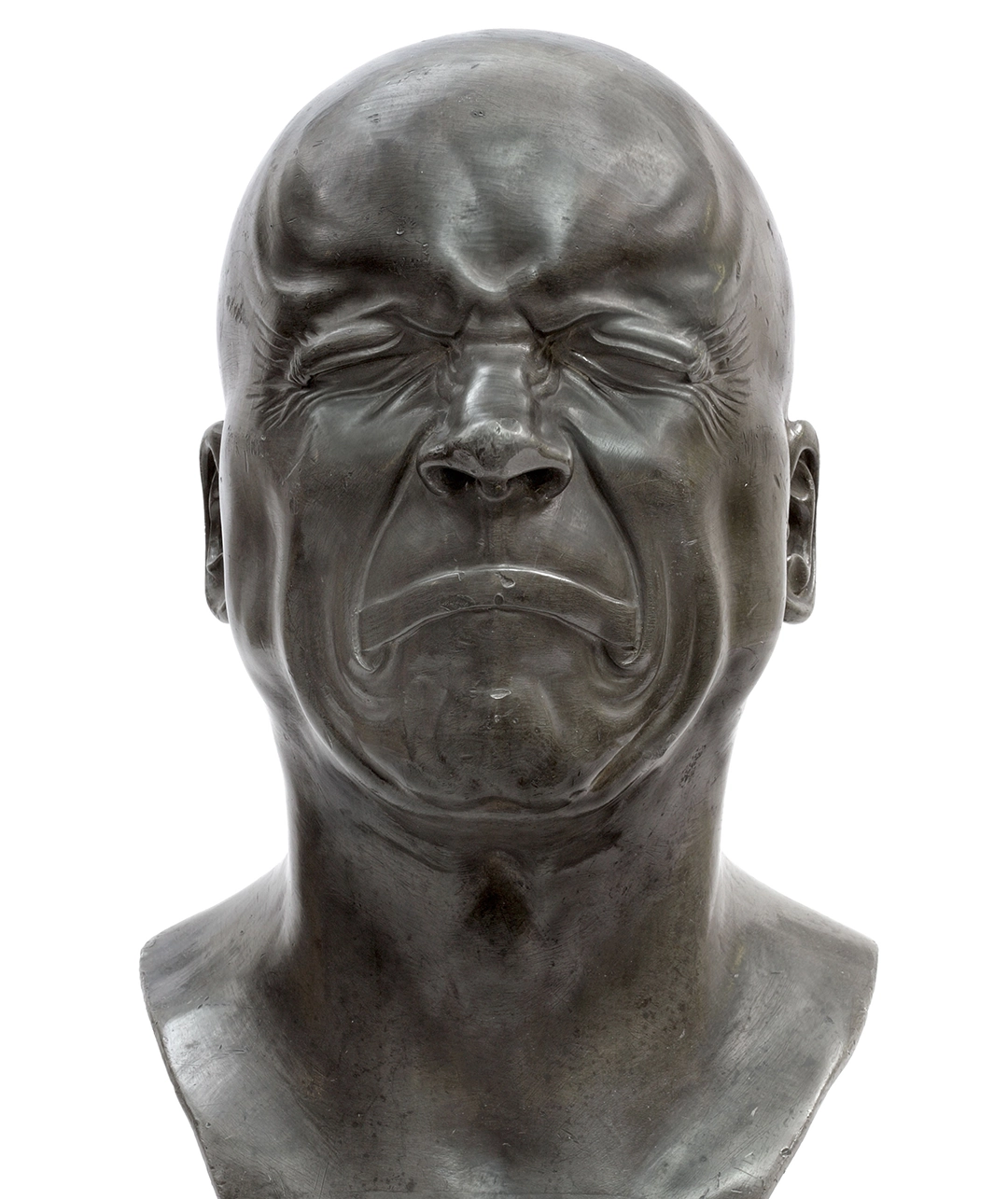

Messerschmidt is celebrated for his “character heads,” a series of metal and alabaster busts marked by extreme facial expressions—grimaces, taut musculature, tremulous contortions—that probe the psychological and the grotesque. Though in life he worked as an academic sculptor in Vienna and collaborated on imperial projects, he owes his fame to this series of heads, now seen as a precursor to modern explorations of psychology and expressivity in art.

Miguel Rodez is a Miami-based, self-taught multidisciplinary visual artist whose work—covered by The Miami Herald, El Nuevo Herald, Frommer’s, and other outlets—is defined by a poetics of texture: dense, tactile surfaces, often on circular “tondo” canvases, with assertive brushwork and pigment-rich iridescence. Moving fluidly across drawing, monotype, painting, installation, sculpture, and fine-art photography, he develops concept-driven series that probe visual memory and the drive for emancipation: Twentieth Century Masters (monumental round portraits of twentieth-century artists), Imagine Liberation and Escape (mappings of freedom), Floral Sensuality (a masculine rejoinder to O’Keeffe), Sweet Vibrations (color and rhythm as score), and Monumental, featuring the 20-foot kinetic sculpture Lucky Link. His installation Forever Dalí—four large-scale iterations staged in a deep hallway—grants the Catalan master the eternity he sought and distills Rodez’s aim: to restore portraiture and form to their affective force as an archive of the human.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog and enjoy its content, you might consider contributing to its upkeep. Any amount, no matter how small, will be warmly appreciated

Founded in 2021, Echoes (Notes of Visual Narrative) invites everyone to explore together the visual codes that shape our world—art, photography, design, and advertising in dialogue with society.

Copyright © 2025 r10studio.com. All Rights Reserved. Website Powered by r10studio.com

Cincinnati, Ohio

Comments powered by Talkyard.