Human genius can be observed in many of its works. Nowhere is it more detectable than in the arts: music, literature, and the visual arts. As a species, seen from above, we are all fairly clever. But some are—or were—truly exceptional. What did they require to rise above the rest? What made them singular, beyond the reasoning most of us share?

Perhaps prompted by a timely confession—or by something closer to a revelation tinged with the paranormal—a journalist from El Español published today an article suggesting that sharing every moment is no longer the axis of the digital experience. It reads as if announcing a trend I cannot find anywhere. Perhaps it is simply that my generation, the people I follow and who follow me, are no longer inclined to chase trends.

This article has little of true interest. What catches my attention, however, is the way its original content has drifted from one outlet to another, as if there were nothing else in the world worth recounting. Perhaps it belongs to a secret chain of good fortune. This is my extract of an extract of yet another extract, and so on, until the original author dissolves into the distance. Take it as a nocturnal diversion and as a reiteration of the open secret that most cultural blogs venture into the fields to harvest the grain that will be baked into the bread of the mornings to come.

This past weekend, Annex Gallery carried out a working visit to Louisville, Kentucky, with the purpose of attending a talk offered by several Cuban artists on the challenging process of sustaining their creative practice within an economic, social, political, and even climatic context radically different from the one they had once known. The conversation took place at noon in the main hall of Louisville Visual Art and extended for nearly two hours. Four Cuban artists from the group engaged the local audience in dialogue about their experiences as emigrants while also delving into specific aspects of their work.

Leafing —digitally— through the latest issue of Tech Life magazine, I come across this advertisement for Luminar 4. I was almost seduced—abducted, rather—by the promise of a digitally retouched future.

A brief investigation confirms that Luminar is a photo-editing software developed by Skylum. It is built upon artificial intelligence and stirs considerable curiosity in the market of credulous souls, among the devotees of technological tinsel and those with very little resistance to the allure of advertising.

For those arriving from South Florida—particularly from cities like Miami—Michael Coppage’s exhibition at the Annex Gallery may resonate differently than it would for a viewer from the Midwest. This is not to suggest a hierarchy of readings, but rather to acknowledge that the lived experience of Caribbean and Latin American diasporas, especially those who have made a life in Miami, offers a particular lens through which to approach this work.

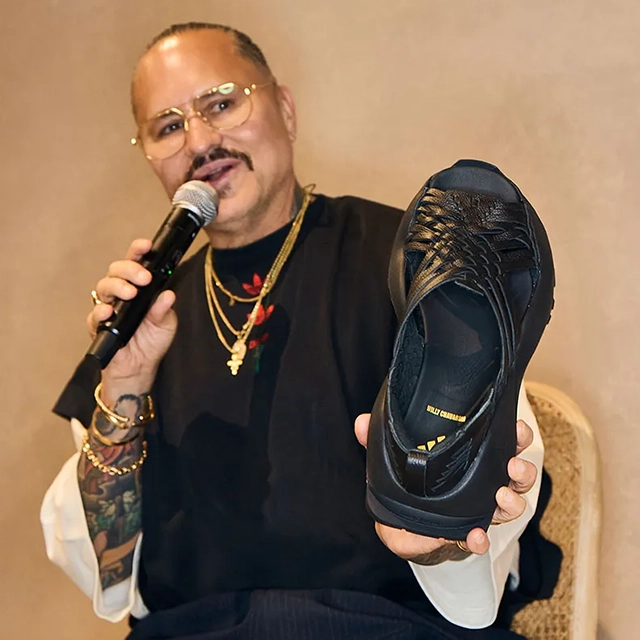

American fashion designer Willy Chavarría, in collaboration with Adidas Originals, introduced the Oaxaca Slip-On, a black-molded, open-toe shoe whose aesthetic directly recalls the huaraches of Villa Hidalgo Yalálag, Oaxaca. The controversy erupted when it came to light that the shoe was being manufactured in China, and that the communities responsible for the craft had neither been consulted nor acknowledged in the creative process.

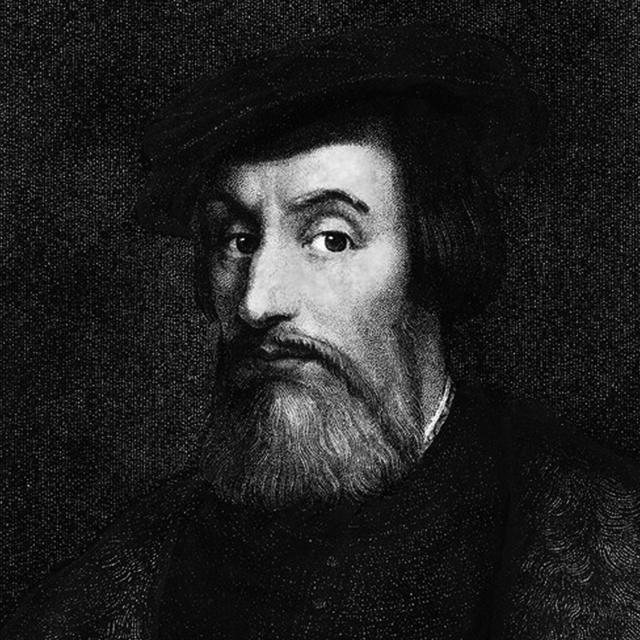

In the cloistered hush of an archive room, where light is meted out so as not to wound the paper, a witness from another world surfaces once more: a sheet written and signed by Hernán Cortés on February 20, 1527. Five centuries have passed since the ink was still wet; more than thirty years since it was wrenched from the collection safeguarded by Mexico’s National Archives and disappeared without a trace.

A few days ago, I published a review of an exhibition held in Cincinnati, where the banana—liberated from its role as a trivial fruit—rose as an object of symbolic power, invested with a political density far exceeding what its modest morphology might at first suggest.

There is always that day in October or November when we sense, with unnerving clarity, that a definitive seasonal shift is approaching. In South Florida, such a prelude might be dismissed as a joke; here, in the North, it must be taken a little more seriously.

Throughout my life, I have felt a peculiar pleasure whenever I’ve had the chance to witness a birth. These beginnings—first steps, embryonic shapes of future realities—emerge every minute, every second. They are part of the unending dynamic of existence in the physical realm. Most will go unnoticed, for only God can foresee the majestic tree that may rise from a given blade of grass.

I've known Leticia for so many years that I can’t quite find the thread of the memory. What I do remember—clearly—is that while she was studying design, I suddenly realized she would never be a designer. Because she was an artist, and because she couldn't, wouldn't, and had no interest in being or doing anything else. I can’t recall the first time I saw her work either. But what I do know is that her work has been orbiting my gaze for a very long time, as if it had always been there—lurking, silent, waiting for unsuspecting, gentle eyes.

When Harry Belafonte released his famous Day-O (The Banana Boat Song) in 1956, he did not intend to celebrate tropical joy or offer a festive anthem to liven up Caribbean cocktail parties in white suburban America. The song—based on a traditional Jamaican work chant sung by night-shift dock workers loading bananas while waiting for the tally man to count their labor at dawn—is, in truth, a weary prayer, a rhythmic lament. Its upbeat tone masks an exhausting, underpaid routine marked by waiting and invisibility.

Leyva is a Cuban artist whose life and work are deeply marked by persistence, reinvention, and resilience. What is truly singular is that, even through transformation, his voice remains intact.

God knows why I tend to read the BBC’s digital edition late at night. Perhaps because I enjoy — and at the same time, not entirely — its concise and direct style. It does, however, offer compelling articles on themes or events that larger media outlets often overlook. Georgina Rannard, for instance, published a captivating piece (in its English version) about the ancient practice of tattooing on the Siberian steppe.

A staggering percentage of its so‑called informative content is either false or, at best, inaccurate. Today I stumble upon a post about the alleged auction—at Christie’s—of an AI‑generated work. I read and save. The note focuses more on the controversy it sparked than on the sale itself, perhaps because uproar, confrontation, and intellectual skirmishes attract far more attention than the artworks themselves.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog and enjoy its content, you might consider contributing to its upkeep. Any amount, no matter how small, will be warmly appreciated

Founded in 2021, Echoes (Notes of Visual Narrative) invites everyone to explore together the visual codes that shape our world—art, photography, design, and advertising in dialogue with society.

Copyright © 2025 r10studio.com. All Rights Reserved. Website Powered by r10studio.com

Cincinnati, Ohio